PUTIN’S SHAKESPEAREAN DEMONS

Geopolitics will take you only so far in explaining foreign affairs. The more important element is Shakespearean. Ukraine is a perfect example.

Geopolitics will take you only so far in explaining foreign affairs. The more important element is Shakespearean. Ukraine is a perfect example.

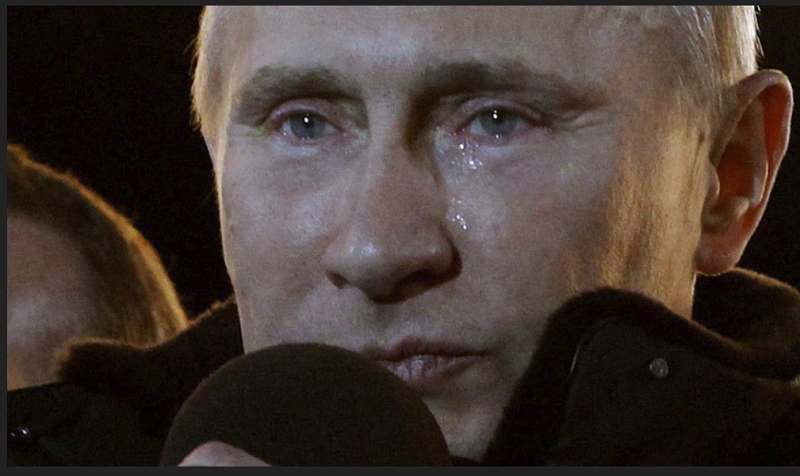

Ukraine is engulfed by Russia on the north and east, its history and language entwined with its neighbor’s. But the greater part of the story concerns the personality of Vladimir Putin. The geopolitical argument that Mr. Putin invaded Ukraine because the North Atlantic Treaty Organization was expanding completely disregards the Russian leader’s Shakespearean demons.

Mr. Putin’s decision to invade represented not the collective thinking of the Russian elite but his own thoughts. Many oligarchs and security heavies near him were as surprised by the decision as people in the West. Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, pressed by an oligarch to explain how Mr. Putin could have planned such an invasion without his inner circle knowing, reportedly replied: “He has three advisers. Ivan the Terrible. Peter the Great. And Catherine the Great.”

Given Mr. Putin’s paranoia, isolation and delusions of grandeur, the question arises: Would Europe today be at peace with Mr. Putin’s Russia had NATO not expanded east after the Cold War and had there been a Western guarantee of recognizing Russian interests in Ukraine? Certainly not.

The explanation for this lies in what would have been the internal situations of the states of Central and Eastern Europe—from Estonia south to Bulgaria and including Poland and Romania—had none of them joined NATO or the European Union.

Having suffered nearly a half-century of communism, and in many cases having lacked a robust middle class before Nazi and Soviet occupation, those former Soviet bloc countries might have remained basket cases, with poverty-stricken rural areas and nasty, unstable politics in the capital cities. That would have left all or most of them vulnerable to Mr. Putin’s mischief.

One of the biggest canards in Washington is that the U.S. would have been better off without NATO enlargement. Take Moldova, a country that is Romanian-speaking and part of historic Greater Romania, yet never admitted to NATO or the EU.

Romania has become a strong and stable state for the first time in its modern history, under NATO and EU tutelage and despite the Stalinist ravages of the Ceaușescu decades. But Moldova is weak and tottering—and a likely victim of destabilization by Mr. Putin’s Russia. Without NATO and EU expansion eastward over the decades, there might now be a few Moldovas between Germany and Russia.

Success in foreign policy isn’t only about the good things that do happen but also the bad things that don’t happen. What hasn’t happened in Europe because of NATO expansion is broad-based instability. Imagine the condition in the heart of Europe today had NATO’s boundaries remained frozen after 1989.

NATO and the EU have created many durable bureaucratic states with reliable militaries in Central and Eastern Europe able to do their part to withstand Russian aggression. The West has grown in both economic and political might. Thus the business of World War II and the Cold War has been closed.

flirts with authoritarianism and Bulgaria is a weak state, but they are the fixable exceptions. If Russia’s military situation in Ukraine were to deteriorate dramatically, it is possible that the opportunistic Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán would re-embrace the EU and its democratic standards.

NATO expansion throughout Central Europe was virtually inevitable because of the decisive and one-sided way the Cold War ended, just as the wars in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s encouraged the West to expand NATO to Romania, Bulgaria and Albania so that they wouldn’t be stranded on the other side of the Balkan battlefields.

Put another way: Had the West not expanded NATO and the EU to the east, we would now be fighting for Poland instead of for Ukraine and Belarus, as Mr. Putin surely would be breathing down the neck of every country between Berlin and Moscow.

Ukraine would long ago have been under the heel of the Kremlin. Germany would have drifted further toward neutralism, requiring a close relationship with Russia not only for natural gas but to manage its borders with Poland and the Czech Republic—had those countries not become members of NATO and the EU and been susceptible to greater Russian influence.

We are now fighting to complete the Intermarium, Latin for “between the seas.” That is, the Baltic and Black seas—a belt of democratic states, from Estonia in the north to Ukraine in the south, to protect against Russian imperialism. We owe this post-World War I concept to the Polish statesman Józef Piłsudski, who envisioned it as a defense against Germany, too. Germany is now a longstanding ally.

With Russia defeated in Ukraine, the purpose of the Intermarium will have been accomplished. This is all about geopolitics until it is all about Shakespeare, since a Russia without Mr. Putin would, however unstable, at least have some possibility of becoming a normal country.

Let’s not forget Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, another Shakespearean character, without whose charisma and dynamic leadership Ukraine might never have mustered the will to resist Russia on the battlefield. Geopolitics gets you only so far.

Robert D. Kaplan holds a chair in geopolitics at the Foreign Policy Research Institute and is author, most recently, of “The Tragic Mind: Fear, Fate, and the Burden of Power.”