KEEPING YOUR SANITY BY UNDERSTANDING WHAT MONEY IS

Last Monday (7/25), Jack’s Glimpse, The Money That Made Us Human, fit so well with my Sanity column on The Virtue of Trade and Money that I’d like to expand on all that this week. Here we go.

One day in East Africa, deep in our primitive past, an exceptional innovator carved a palm-sized, pear-shaped, razor-sharp axe head out of stone. This must have revolutionized the ability for him and his band of hunter-gatherers to hunt, butcher food… and to wage war on their neighbors.

This was over seventeen hundred thousand years ago, long before homo sapiens had even appeared on earth. Over time, others learned to copy this stone ax head, and the innovation spread over Africa, then across Asia and into Europe by pre-humans known as homo erectus, or “upright man.”

The identical design of what archaeologists call Acheulean hand stone axes has been commonly found at many different archaeological sites throughout different eras, and up to about a hundred thousand years ago they were still being made, in exactly the same way, by our homo-sapiens ancestors.

For over a million and a half years, as far as we can tell from the archeological record, this was the extent of human and pre-human innovation. That was it! Nothing new for a over 1,600,000 years.

Then, something revolutionary happened; something that changed the nature of humanity, and transformed our cultural growth as a species… the world’s first jewelry was invented. By us.

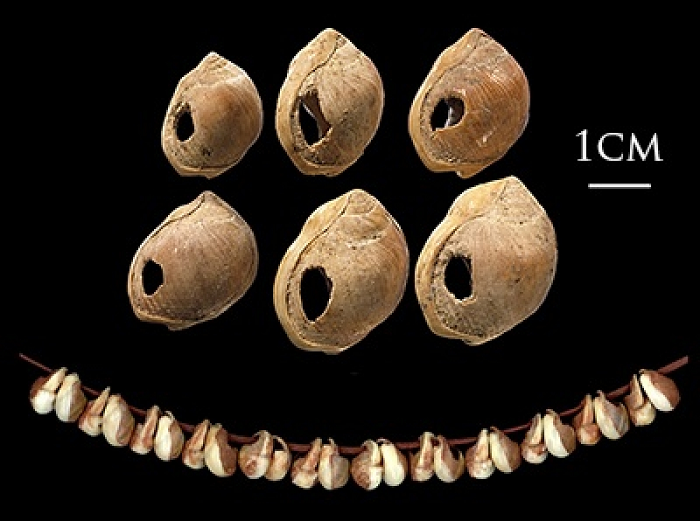

One day, about 90,000 years ago, something new appeared in Africa. Beads. Beads, made of the shells of a tiny marine snail called Nassarius gibbosulus, painted, and with tiny holes drilled in them.

And when I say, “by us,” I mean that it was in Africa that we – homo sapiens – evolved from versions of homo erectus some 250,000 years ago, replacing all other proto-hominids in Africa. And we stayed there in Africa, not going anywhere else in the world. Then someone on the shore of Mediterranean Algeria started making necklaces of these tiny shells.

What was truly transformational, though, wasn’t the beads themselves, it was the mystery they presented. How did beads found at the seashore make their way hundreds of miles to the south? That’s Sahara Desert now, but back then it was a green eden, a hunter’s paradise.

The shell beads were brought there. Not as some one-time haul from a murderous raiding party – which would been the most likely way up to that point for one tribe to get something from another tribe.

No, these beads were part of something new; something that from any evidence we currently have, had never been seen on the face of the earth before; something we take completely for granted today:

Trade.

This was the first evidence of humans trading with one another. These shells weren’t just jewelry, they were likely used as the first money, as well.

Sure, lots of animals do reciprocal things, like picking the lice out of each other’s hair, or helping each other with a hunt. But to trade different things or actions of different value was brand new. I have some meat, you have some berries, and we figure out a mutually agreeable amount of each to barter so we’re both happy… win/win.

But then to use something as a medium of exchange – the money we use today, or the painted Nassarius shells our distant ancestors used in Africa – that accelerated the benefits of trade exponentially.

Eventually, our ancestors developed intricate trade networks, inspiring innovation and cooperation that had never been possible before. In a very real sense, trade, as Jack says, is what has made us human. It encourages the better angels of our nature – to borrow the title of a magnificent book by Steven Pinker on why violence has declined.

Trade, among other things, encourages curiosity about other people – and therefore empathy.

When we trade, there’s a benefit to wondering what other people – who are not members of our immediate family or tribe – are interested in, how they communicate, what their habits and customs are, how to approach them in a peaceful and respectful manner, and what we might bring to them to exchange for something they have that we want.

Trade encouraged a whole dimension of curiosity that would never have occurred to our ancestors otherwise.

Before trade, if people from one tribe encountered people from another tribe, the most common interaction would have been war, along with maiming, torture, and slavery.

Trade had and has today the effect of expanding humanity’s moral circle, to include people outside of our own group, our own familiar culture, within our own circle of concern and empathy. It’s one of the central reasons for our development of abstract thinking and reasoning, and our continuing cultural growth toward greater peace, curiosity, and integration as a species.

Trade has also opened up something else brand new to the world: the practice of specialized creative, productive work.

What can I create today? What can I build today? What kind of service can I provide that other people aren’t yet providing? These are questions that have also transformed us, and expanded our minds and abilities to a degree most of us also take for granted today.

We can live almost anywhere, from the depths of the oceans, to the frozen arctic, to the surface of the moon – even nowhere, in the vacuum of space itself.

Our average life span has grown, in just the last century in the United States, from under 50 years old, to nearly 80.

Trade, and the development of specialized creative, productive work, have made all of this possible. They have made what were at best fantastic dreams just a handful of decades ago, into the stuff of everyday life today.

Trade and productive work make what we do mean something – they give us the incentive to think big, to solve problems, to ask uncomfortable questions, and to sometimes risk everything on an idea.

The creation of value is what work is all about. Maybe it’s the value measured in an amount of money; but it can also be the excitement of making something work, solving a problem, pioneering something new, or improving the lives of lots of people.

Specialized creative, productive work within a system of trade allows us to spend most of our time getting very good at what we do – because we get paid, and so we can earn what we need to live by doing it. It’s also a means of earning success; and earned success is one of the great joys of life.

It’s great to have money, to be able to buy what we want, do what we want, and create a sense of security in a volatile world. But money is much more than that.

Understanding what money is, and what a powerful, benevolent, and humanizing force the trade that money facilitates has been, can help us to appreciate the meaning that our work has for us, the good that money can bring, and the value of skillfully building and shepherding our investments.

PS: My new course, Mastering Emotions, Moods and Reactions can help you with this part of your life in much greater detail, with deep understanding and practical skills for mastering these systems and living well. You can get it now with a deep discount, for $99, if you use this code: LB99.

Joel F. Wade, Ph.D., is the author of The Virtue of Happiness, Mastering Happiness, his new course, Mastering Emotions, Moods and Reactions, A Master’s Course in Happiness, and The Mastering Happiness Podcast. He is a marriage and family therapist and life coach who works with people around the world via phone and video. You can get a FREE Learning Optimism E-Course if you sign up at his website, www.drjoelwade.com.